Autobiography of Amos Elbert Hinks

Home >> Features >> Autobiography of Amos Elbert HinksAmos Hinks wrote an autobiography, or more precisely, worked on it. While rummaging through his files, I discovered a lot of pre-written material, including multiple versions of some parts. I took this material, sorted it into a logical sequence, and picked out the best version in cases where he had written the same story more than once. I also added a few photos. The result is the Autobiography of Amos Elbert Hinks, in his own words.

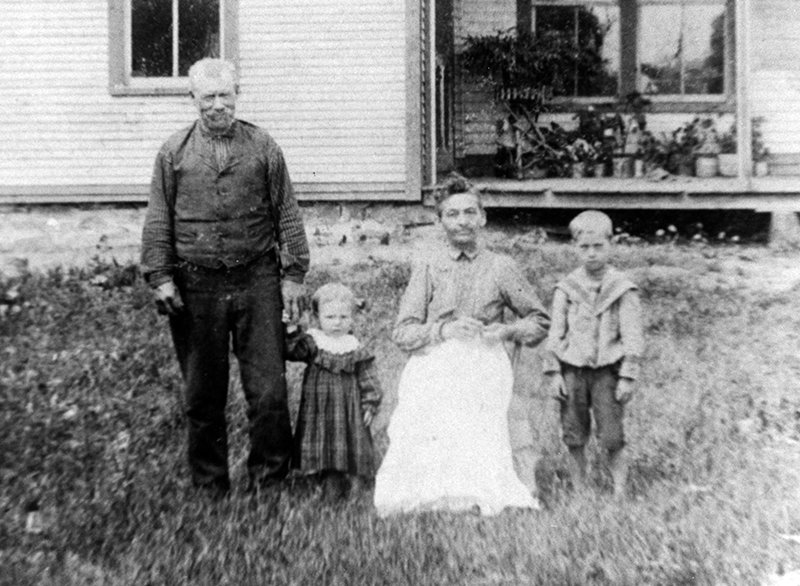

My Father was a Canadian, who crossed the border into the U.S. He had heard of the many opportunities to work for the farmers to clear land, build fences, and put in crops. My Mother was a farm girl with an eighth-grade graduation, who had a lover go West and never return, and another go down East and never return, so when this well-built Canadian with a mustache came along, they formed a pair, and were married. They framed the marriage license, and hung it on the wall, Thomas Hinks to Olive Lydia Lafluer.

Thomas worked a while for his Father-in-Law Joseph Lafluer in Burke, a town in northern New York, 3 miles from Burke Village, and about 4 miles south of Canada. Soon he and Olive purchased a 75-acre farm about a mile from Olive’s home, and Thomas became a dairy farmer. In their own house, God blessed them with sons Joseph and Warren, and a daughter named Cora.

On June 29, 1899, Mother made breakfast of the usual old-fashioned oatmeal, and a doughnut for everyone, and a cup of tea for Father. That day, a friendly neighbor notified the Doctor by horse and buggy at his home about three miles away, and the Doctor soon came by horse and buggy. It was hours of suffering by Mother, but with the help of the Doctor, a new babe was born. It was a boy, but he spent the next few days unnamed.

One Sunday, as my brother Warren was learning the names of the books of the Bible, he came to the name Amos. Warren liked the name, and he mentioned it to my parents. Mother, who knew her Bible well, knew of God’s servant Amos, who warned the Israelites that they were living in sin, and must repent to prevent disaster. Father then remembered that he had once worked for a Canadian named Amos, who he respected. So, the boy was named Amos Elbert Hinks.

The family welcomed Amos. Mother accepted the daily change and washing of diapers on her washboard. It was not long before Mother noticed that my belly had not properly healed. The Doctor did not know what to do to close it, and it remained a seeping sore. They were probably hoping that it would cure itself, but such was not the case. As I grew, I would walk with folded arms because it was sore and hurting.

When I was a babe in arms, my 11-year-old brother Warren would relieve Mother by taking me in his arms, and while sitting in Father’s rocking chair with one of his legs over the arm of the chair, would sing to me a little Irish song (I do not know where he learned it):

Oh! Bridget, ye are so handsome,

And your figure is so complete.

Your waist is so round about,

You are so tall and straight.

And if you’ll only marry me,

I’ll never care a tall,

If there never grew a Murphy,

In the town of Don-e-gul.

I was about three years when my mother made pants for me. Up to that time, I wore a checked dress. Now-a-days a boy is dressed in overalls before he is a year old.

On June 28th, when I was five years less one day old, Dr. Stickney came to help deliver a baby boy. He was named Alton. His bed was a long clothes basket until about one year old, and then he and I slept on the same cot in Mother and Father’s bedroom, off from the kitchen, he on one end, and I on the other.

When I was five or six years old, Father had a painful problem with his hip. As he now had two boys who could milk the cows and do other farm chores, he went for treatment at a Catholic Hospital in Ogdensburg, New York, a terminal of the Rutland Railroad, along the St. Lawrence River. The doctors did what they could, and after his operation and a few days at the hospital, it was decided that I too should go to the hospital to see what could be done about my navel.

The doctors operated to close my navel, and I was given a bed in the men’s ward, a large room with patients in 12 to 16 single beds on each side. A five-year-old would normally be in the children’s part of the hospital, but I was placed beside my father. I had Father to my left, and a man named T. P. Griffith to my right.

Every day and night, a Catholic Priest would filter through the ward. Several times I woke up in the morning to find a large Canadian penny in my bed, placed there by the Priest. A large Canadian penny is about twice the size of a U.S. penny. I wish that I had kept one.

I saw my first flush toilets at the hospital. A container holding a couple gallons of water was attached to the wall near the ceiling. To flush the toilet, a chain leading up to the water tank was pulled, causing water to rush down, and flush the toilet.

After Father left to return home, I became friends with Mr. Griffith. Mr. Griffith was about 65 years old, and lived in Richville, New York, another place along the Rutland Railroad. The next summer, when both of us were healed, Mr. Griffith invited me to visit him, so I was put on the train in charge of the conductor, to be put off at Richville Station, two miles from the actual town. Mr. Griffith had a horse and carriage, and he drove people to and from the railway station. I was able to ride along with him, and I stayed about a week.

One day, when Alton was three to four years old, he did something for which Father thought he should be punished. As the narrow cedar shingle was about to be applied, I, believing that Alton did not deserve to be punished, grabbed the shingle from Father, and ran. Father was so surprised, that Alton was freed, and thus never received what was intended to warm his rear end. Alton will never know why Father let me get away with it.

Another thing I remember quite well was a time when I was about six or eight. An uncle to Mother, whom we called Uncle George, knew how to mesmerize another person. Mesmerizing is when one person can gain influence over the will and nervous system of another. With the idea of helping Father’s bad leg, he would mesmerize Father by having him look at an object like the bright head of a lady’s hat pin. Uncle George would gain control, will over Father, and have him down on the carpet in the parlor picking strawberries. This is no baloney, except there were no strawberries.

We attended church at the Coveytown M. E. Church. It was a branch of the church at Burke Village. Our pastor preached at Burke Village every Sunday morning, and at our church in the afternoon. We had Sunday School before the preaching. The building was 1¼ miles from home. Behind the church building were sheds where members kept their horses while they were in church. After the preaching, and before the last song, there was a testimonial meeting, when some of the older members stood and told what the Good Lord had done for them. Rev. Campbell was one of the two men that I as a boy admired; the other man was my High School Principal.

I attended school at District #15, starting at the age of five, and going with my sister Cora who was then 12 years old. School started at 9 AM, with 15 minutes of recess midmorning and midafternoon, one hour for lunch at noon, and ended at 4 PM. There were about eight to ten pupils when my older brothers went to school, but sixteen years later when my younger brother went for his last term, he was the only pupil.

It was a one-room schoolhouse about a half mile from home. The schoolhouse was about 20 by 30 feet in size. One entered the building by going through a woodshed where 24” lengths of dry wood were piled, enough to last through cold weather. At the left, just inside the door, was the teacher’s desk, about eight feet long, holding a pail of water and a dipper for the pupils to use. The large box stove was in the center, behind which was an aisle with rows of seats on each side. Toilet facilities were two small buildings on each side, for boys and girls respectively. There was a large yard in front used for tag or baseball during recess and at noon. The flag pole in the center of the schoolyard in front was where we learned to pledge allegiance to the American flag.

Father was the school Trustee, and he hired the woman teachers who usually lived with a family in a house close to school. Sometimes on Friday, the mothers came to visit when we recited pieces or read a composition.

Our first grade began with a reading chart attached to the entrance door. It had lines like, “I see the dog,” “The dog runs fast,” etc. As the years passed, the school provided Barnes 1st Reader, 2nd Reader, 3rd Reader, 4th Reader, and finally the 5th Reader. Then you graduated and were through going to school, or went on to High School at Franklin Academy in Malone. A Regents Examination issued by the State of New York had to be passed or studied further if entering High School.

A farmer living about a mile away, had a sugar bush, and made maple syrup and sugar during the season in March. Maple sugar parties called sugar-on-snow socials were common, with one or two during a season. At the party, each person was given a large soup dish of hard packed snow, and a sauce dish of hot maple syrup that had been boiled. A spoon was used to sprinkle the hot maple syrup on the snow. The maple syrup cooled to form a wax, which was eaten. Nothing else was served at these parties.

As a lad of eight or nine, I had visions of how I could make maple syrup. Below the creek, a neighbor had a few young maples. Having gained permission, I had to make wooden spiles to drive into the 7/16” holes that I drilled 1½” into the trees. A bucket was attached to each tree using a nail. I tapped six or eight trees, and at least got enough to carry sap the quarter mile to Mother’s kitchen stove. More fun.

As we lived on a farm, there were always little jobs that I could do, like feed the calves, or go bring the cows in from pasture in the morning. I would do this barefooted in the summer, and warm my cold feet on spots in the pasture where the cows had lain all night long. There was a fenced-in lane about 16 feet wide from the pasture to the barnyard. I helped milk the cows every morning and night when I was 11 to 12 years old. Then we had a hand-crank separator through which milk was passed to separate cream from skim milk, cream from one spout and skim milk from another. Cream was kept cool to be taken to the butter factory every other day.

There was another job that I called ‘helping Mother fry the doughnuts’ that were always part of breakfast. Mother would roll out the dough to ½” thick. With a doughnut cutter, I cut out the dough, and left a hole. Mother then dropped four or five pieces into an iron kettle half filled with hot lard. The dough would fall to the bottom of the kettle until the yeast in the dough caused them to rise to the top of the molten hot lard. There the doughnuts would fry on one side until properly browned or done, and then I would turn them over with a fork to fry the other side until they were ready to remove.

When the milking was done, the cows were sent back to pasture, and the horses fed, it was time for breakfast. We all sat down together, and Father or Mother gave thanks, with all heads bowed. Oatmeal and tea and toast and a doughnut. After breakfast was over, Mother read a chapter from the Bible, and then we all kneeled at our chairs, and Father or Mother asked God’s blessing on the day ahead.

After breakfast, we fed the hogs skim milk and corn.

Where did we get our drinking water? Our two wells were dug long before my time. There was a well at the barn for cows and horses. It was about 12 feet deep, with a diameter of 4 to 5 feet, and walled up inside using stone without mortar. The well for the house was dug down from the basement about 6 to 8 feet, with a diameter of 5 to 6 feet, and walled with stone. This well was located so that the hand pump was in the pantry on the 1st floor. Neither well gave us any trouble. The barn pump was made from a log 12 to 14 feet long, a diameter of 8 to 9 inches, and a 4-inch hole bored its entire length, had a handle about 3 feet long. Water at the barn was pumped into a wooden trough from which cattle and horses drank.

The kitchen stove had a firebox adapted for burning wood pieces, with four round cast iron griddles about 12 to 14 inches long. One was removed to add wood. At the right end of the stove was a reservoir for hot water, and the oven was between the firebox and reservoir. The stove heated the upstairs room by means of a stovepipe leading to the chimney. There was no window in this upstairs room, although I remember a spinning wheel and a spool on which to wind yarn.

We had a wood lot about two miles from home, which was our source of wood for cooking and heating the house. Trees up to 6 inches in diameter were cut in lengths about 14 to 15 feet long, loaded on bobsled, and hauled home with a two-horse team when snow was on the ground. When the year’s supply had been brought home, a man brought a circular saw that was powered using two horses on a moving incline, and the long lengths were all cut into pieces 12 to 14 inches long and thrown on a pile.

In summer, hay was cut with a mowing machine, and after a day of drying, it was ready to rake. That was a good job of making piles of hay across the field. It was then gathered in forkfuls, and loaded on a hay wagon, with one person on the ground, and the other on the wagon.

On Father and Mother’s 10th Wedding Anniversary, the neighbors gave them a large chair for Father, a small rocking chair for Mother, a set of dishes, and a large brass kettle used to boil clothes on the kitchen stove on wash day.

Before I was born, Father hired a carpenter, and made an addition of a parlor, 3 bedrooms, and a clothes closet. This supplied a bedroom for company, and for my two older brothers, and for my sister Cora. A stove in the parlor heated the upstairs by means of a smoke pipe leading to the chimney.

The toilet was a small structure facing south. It had a large 12-inch hole, and a small 8-inch hole. This structure was attached to the end of the wood shed. Chamber pots stored under the beds were used during the night.

The telephone line went through about a mile south of our place. The company told our community of about a dozen farmers that if we would cut and set poles, then they would provide the wires and telephone service. We were all on the same line. Each was assigned a call of long and short rings, made using a small thumb and finger crank on the right side of the phone box. Our ring was a long and a short, and we had to listen for the signal we were assigned. Every party heard all the other rings.

About 1/8 of a mile down the road was what we called ‘the Interval,’ a stream that crossed the road beneath two short wooden bridges. During the summer, it was just a small brook, but in the winter, it overflowed and froze to create a lake about 200-300 feet along the road, on all of which we could skate. Here we spent many happy hours.

Besides the pleasure of skating in the winter, I could not overlook the fun of fishing. There were two kinds of fishing because there were two kinds of fish. The first were suckers that do not move around much, but will stay still close to the bottom, and suck water through the mouth and out the gills. I had a pole with a wire loop at the end. To catch, I slipped the loop over the head, and snared them. I did this while laying on my belly on the plank bridge. Then there were the regular kind of fish that required a pole, hook, line, and sinker, and baited with an earthworm. I had to visit the garden to dig a can of worms.

I usually did not catch more than enough for myself, which Mother would fry after I cleaned them by removing the head and intestines.

When I was about 9 or 12 years old, a calf died, and I was given the job of skinning it. The skin was lightly sprinkled with salt, folded, and the next time we went to Burke Village, the skin was taken along to trade for groceries. We often also traded eggs for groceries.

When I was 12 to 13 years old, I was working for John Langford up the street. The Langfords had a dairy farm with 17 cows for milking. I well remember one night when Mr. Langford was away, and that evening I had to milk all 17 cows. Mr. Langford’s wife Jean was the daughter of Mr. McKensie, who owned the store. The McKensies lived in a house reached by a steel bridge. I remember being on the top floor of the store where the grain was ground.

When I was 13 to 14, I worked for a dairy farmer named Fred Wright. I was still attending school at the District #5 one-room schoolhouse. My special attraction then was Winifred Newton, first love.

Our High School was called Franklin Academy, in Malone, which was eight miles from our farm. In the Fall of 1914, having passed the Regents Examination at District #5, I entered High School at Franklin Academy. It was general practice back then for high school students from outlying districts to rent a room in town, and each week bring a suitcase containing a loaf of bread, a pie, and other food items to last the school week.

The place I stayed in town was a large house, and about four students lived there. Rent for room and kitchen privileges was $1.50 a week. The Mr. of the house was a Railway Post Office Clerk, with a run from Malone to Utica on the New York Central. During the Christmas season, the busiest time of the year, and knowing I could use the money, he suggested that I apply for the 4-day job as Substitute Railway Post Office Clerk.

Transportation varied. Sometimes I went by horse and buggy. Sometimes in good weather I rode my trusty bicycle, on which I built a carrier to which I could strap my suitcase of supplies each week. Sometimes I took the Rutland Railroad, Burke to Malone, eight miles. Sometimes on weekends it was a walk home carrying my empty suitcase. Never did I stay a weekend in Malone.

The first year at High School, I studied Algebra, English I, Physiology, and Bookkeeping. Then a boy named Eldred Hyde, who was my age and lived in Malone, was a special friend. We signed up for the Commercial Course. This had some interesting subjects like Bookkeeping, Writing, Shorthand, and Typing.

My Study Hall seat was in a corner to the rear left. When we were assembled in Study Hall with Principal Fritz Englehandt on a platform in front, at 9 AM he would call, “Alright,” and stand up. He would make any needed announcement, and then lead a song about Franklin Academy or America. He would sit at his desk, ready to help any who might need assistance. He is one of the two men that I held in utmost respect, he and Rev. Campbell, our pastor of the North Burke Methodist Church on Sunday afternoons.

I had heart throbs for a girl named Beatrice Reynolds, who lived in a house near the railroad station in Burke Village. During my fourth year, Beatrice’s parents sent her away to school, apparently deciding our love that year was too serious.

I found work at Malone working for Mr. Hatch, the school janitor, at sweeping rooms. He lived in a large house at the top of Academy Hill. This house rented rooms on the second floor to girls, and the third floor to boys. As I remember, rent was about 50 cents per week, and Mrs. Hatch helped to prepare meals. I lived at this house during my fourth year.

When my brother Warren, 11 years older, started attending Franklin Academy, he also had to go to another school where he had to restudy an 8th Grade subject that he failed on the New York State Regents Examination. At this 8th Grade school, Warren met a teacher who influenced him to change his High School business course to a scientific course. He also entered school activities, such as baseball, football, debating society, and on Monday evenings went to Armory as a member of Co. K, National Guard, all of which are things I chose not to do. After graduating, he took a New York State examination, and successfully passing, was granted a 4-year scholarship to attend Cornell University, where he studied Civil Engineering, which led to successful employment, where he reached the top of his profession. I mention this to provide a comparative structure. I believe Warren’s experience with me at the age of eleven, a babe in arms, gave him a protective shield over me throughout his life, for in his last letter he wrote, “You mean so much to me.”

My first job out of High School was as a typist in 1918 at Washington D.C. The World War was nearing its end, and my older brother Warren still had his arm about me as he suggested I quit, and invited me to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to try locating a more permanent employment. Here I found work in the record department of Cambria Steel Co. I was also welcomed into a church where my brother Warren attended, and his wife Eleanor was a special member of the choir.

One Sunday, a friend in the Pioneer Bible Class and I went for a hike up the B&O Railroad track. This happened to be a very important walk, as a small ad torn from a youth’s magazine caught my eye. It mentioned a B.S. in Engineering – no foreign language required. This is what caught my eye, for in High School I had not studied any foreign language as had my brother Warren.

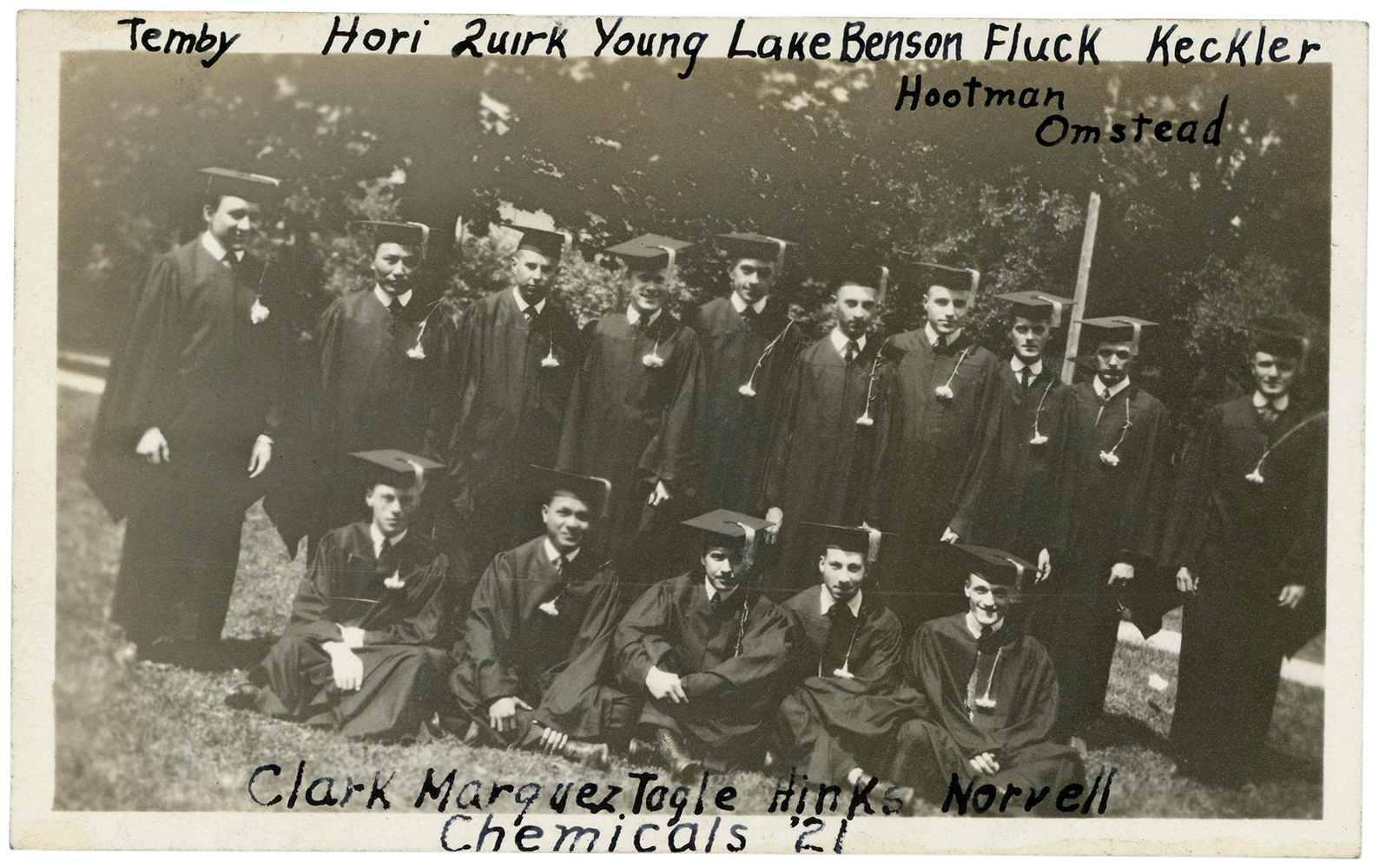

I decided this was my chance, so in the Fall of 1919, with much money, I entered Tri State College of Engineering at Angola, Indiana, as a Chemical Engineer.

For reasons that finances will never explain, I stayed for a class in Psychology. It was an extra semester for new teachers who graduated from High School in May. I considered myself lucky somehow to take Sunday afternoon walks with the pick of the new graduates. One girl took my fancy, but she was taken. The best I could do was go walking with her roommate named Mildred E. Frank.

I returned to Johnstown, where I was given a job at Benzol Laboratory, in a routine testing lab working under Mr. Bisinet, Chemist. I was living with my brother Warren and his wife Eleanor until I moved to the Y.M.C.A., where there was a nice cafeteria.

At the Presbyterian Church, I was a member of the Pioneer Sunday School Class taught by Mr. Hoerr in the morning, and attended the Christian Endeavor Society in the evening, where we met many young folks. One was June, with whom I spent many good times at her home in Ferndale. It seems that another party who lived next door offered greater security, and her interest in me for her boyfriend lessened, and she no longer came to Christian Endeavor.

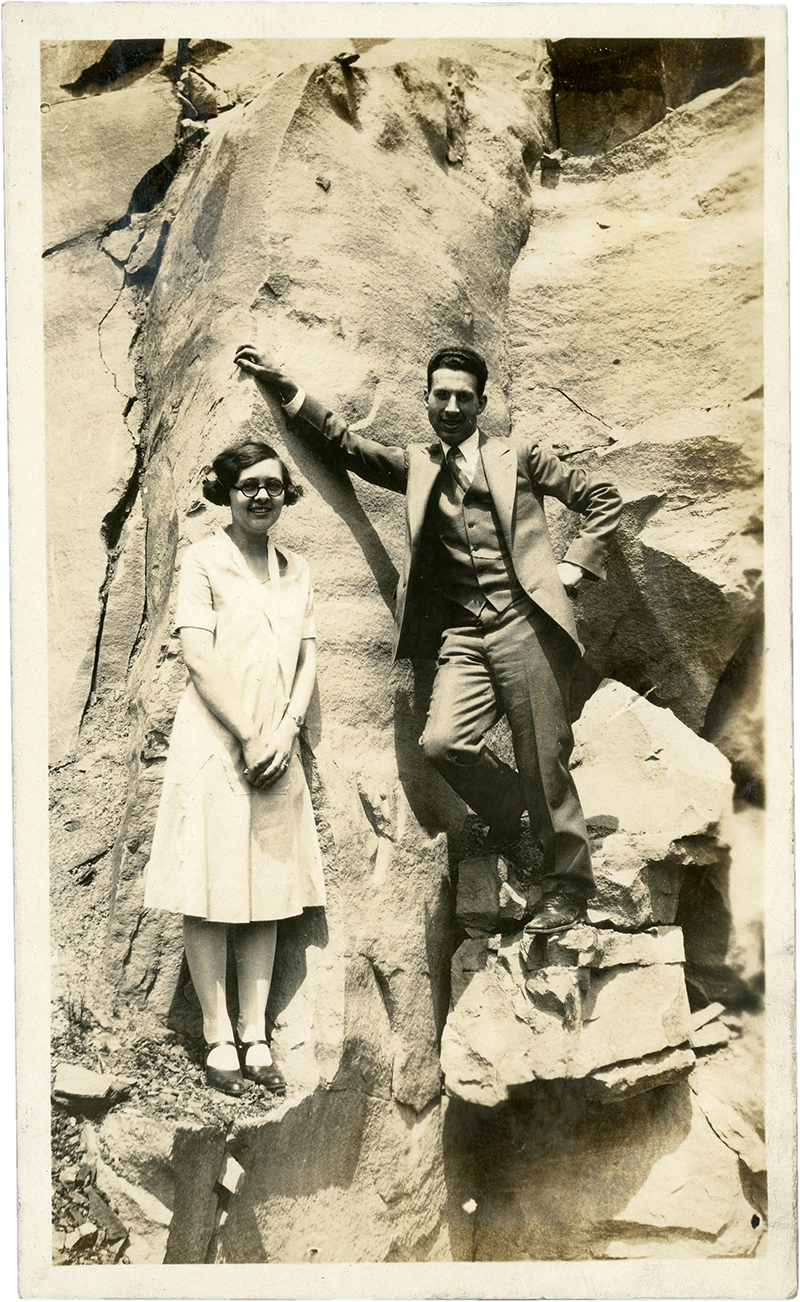

I did not take it so badly, but remembered the girl Mildred, with whom I had no date, but had completed her normal training, and taught at a school located three miles from her home, using a Mexican pony and buggy to travel.

I took a chance, and wrote to her, and welcomed a friendly reply. In the course of time, she was invited to Johnstown when Mother, Alton, and I lived over a garage. I took a picture of her standing against the rocks.

The following year, she moved to Akron, and was by then a point of my interest. She lived with an aunt on Oxford Avenue. So, I quit my laboratory job, and found work at the Star Drilling Machine Co. in Akron, in the shipping room shipping repair parts out all over the U.S.

I worked at the Star Drilling Machine Co. in various positions, including Assistant Purchasing, then Punching Agent, then oversaw factory production. Because rotary drilling was gaining in popularity, our plant closed in 1952 when I was 52. Akron at that time was largely a rubber city where auto tires were made. I was without a job, and prospects were not too favorable at my age.

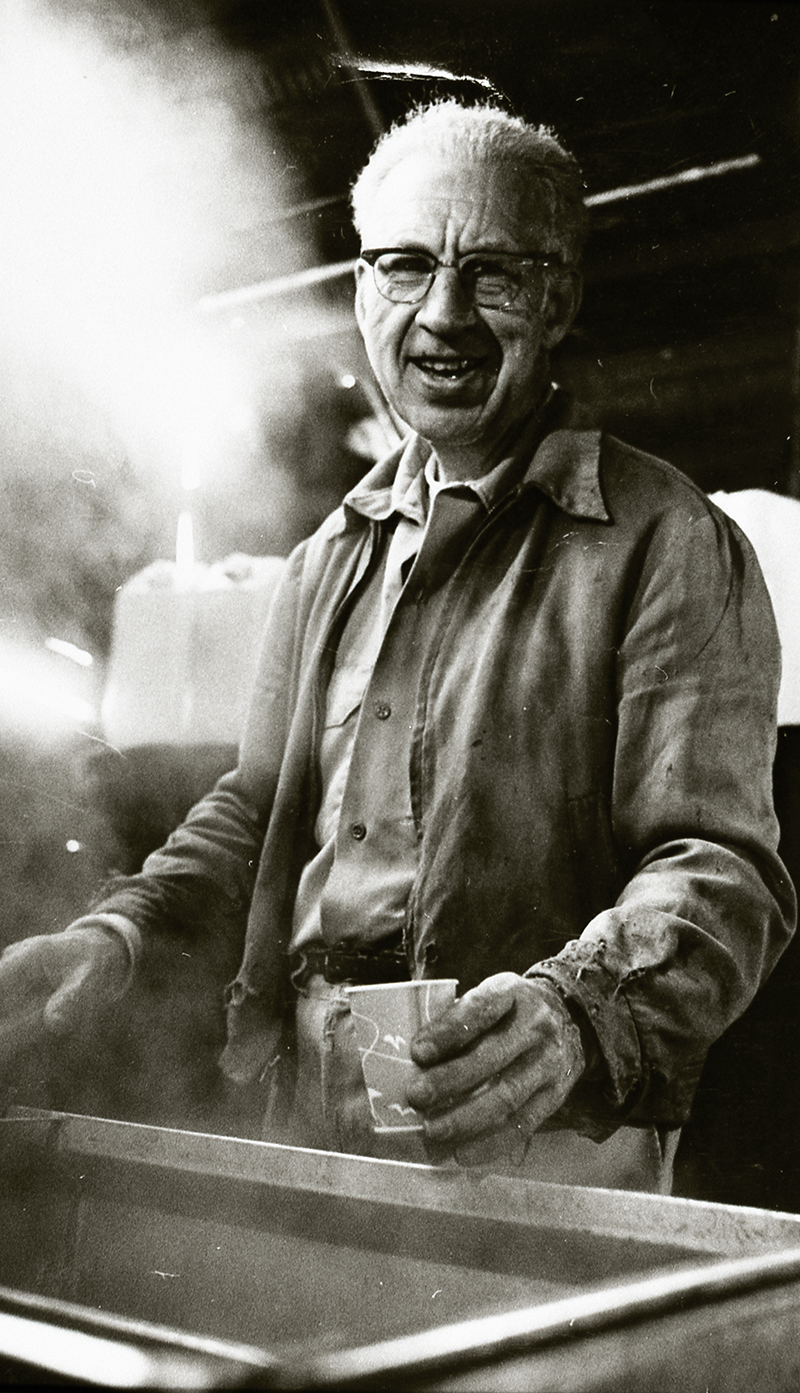

It so happened that the Star Drilling Machine Co. had done some extra heavy heat treating for Mechanical Mold & Machine, especially gun forgings, which were in specially heated furnaces. I was somehow associated with the words ‘heat treating,’ and the Purchasing Agent for Mechanical Mold & Machine of Akron, Ohio, phoned and offered me a job in their plant as a tool room heat treater. This I gladly accepted. It was considered a God send, and thus gave me employment for 15 years. Mildred and I became lifelong friends to Jim and Beulah Reinhold of Wadsworth, Ohio.

These added employment years served well, and gave us encouragement in thinking of a special retirement place in the country, to live and enjoy. In the meantime, we had the idea of making a picture map of the many things we wished to possess, by cutting photos from magazines, and gluing them to a plain sheet of 13 by 22 inch paper. These included such items as a forest path to place at top and bottom, and in between, new friends, a home, sunshine, rain, farm animals such as a cat, dogs, and a cow or two, maple trees, neighbors, flowers, gas, peace, and quiet. We placed this picture map under glass in a frame, named it ‘Treasure Map,’ and hung it in the bedroom.

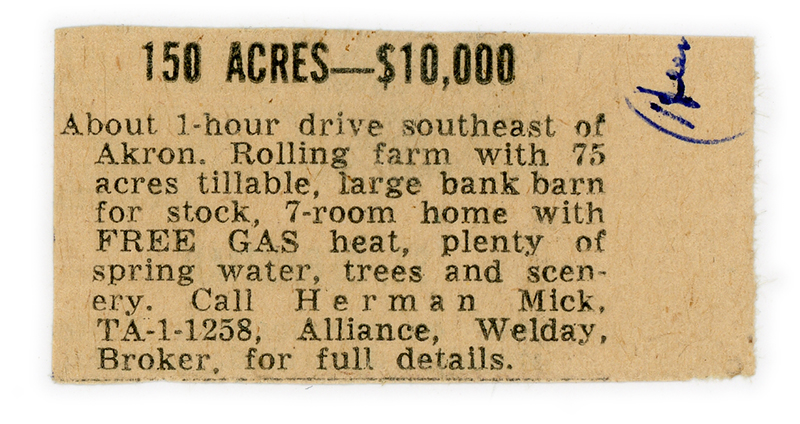

After close to 60 years of work, we started to thank God that we were being directed to the spot of our dreams. Looking in the Real Estate column of the Akron Beacon Journal, we found a property for sale, a farm in Carrollton, Ohio. “160 acres, only house on road – no thru traffic – 1,200 ft. oil wells, surrounded by forested hills, price $10,000 – 60 acres cleared fields.”

It sounded good, so we made a trip to this farm in Carrollton. The husband had died, and the widow was trying to get by. We made a second trip to check data at the courthouse, but we could find no problems. We were interested in the cultivated areas, as there were farmers nearby, and fields could be rented for growing crops. Here was a place that gave us what we wanted, including a chance to make maple syrup and have a few farm animals.

Thoughts of making maple syrup, farm animals, and a bee yard were foremost in our mind, along with enthusiasm of making some alterations to the house, such as a bathroom to replace the fireplace. It just seemed that no one wanted the place at the end of the road, but Mildred and I sure did. The selling price was $10,000, but there was no harm in asking if Mrs. George would take $9,000. She accepted, so it was a deal. Shortly after, we were ashamed, and paid the $1,000 to give the original price asked.

This was in 1963. We were happy to have purchased the farm, but I did not want to quit work so soon. I wanted to work 15 years at the job I had at the time to add to the Social Security, so I continued with my job until March 1, 1969. That means there were about six years when we did not live in the house. It gave us time to change things as we determined to be necessary. The fireplace and fireplace chimney were replaced with a nice bathroom, and cupboards and shelving were added to the kitchen. I also lowered the ceiling in the living room.

A well was drilled, and we added plumbing for a bathroom and shower in the basement. The shower was taken out when Judy Garling gave us her washing machine.

Included as part of the farm were eight 1,200 feet deep oil wells developed by an oil company, but the lease was then owned by a Michigan oil company that walked off the job. There was gas in the oil wells piped to the house furnace, but to use the gas, it was necessary to pump the wells with an electric motor in the pump house. V-belts extended from the electric wheel to fly wheels of a large gas engine to move a flat belt to a unit 18 to 20 feet away, on which one revolution would pump all eight wells. After a year or two, someone stole the electric motor, and we had a fuel furnace installed in the house basement.

We were fortunate a close neighbor wanted to rent the farm for four years, and afterwards a hog farmer rented the farm for another three years. To reach the ten-acre field at the far corner of the farm, the road was a long road starting at twin maples (one tree has the end of a scythe embedded through it, where the tree has grown together.). This farmer tore bark off both trees trying to get discs through between them. I since built a new road divert to the field. There is a special designed gate hung on a pipe in the ground. This gate I built in the house living room. This gate should always be painted and maintained as an important item of note. Call it ‘Grandpa’s Gate.’

In the course of a year or so, all the items on the Treasure Map had become reality, except a dog. Surely such an omission could be remedied without much effort, but there was no occasion to hurry the matter. Mildred said, “Someday we will have a dog. It must be a collie, must be a female, and must be spayed.”

It so happened that our granddaughter and her girl friend, both 14 years old, spent a few days with us that summer. Having an occasion to visit a garage at our local cross roads town, the two girls went along. While waiting in the car along the street, a small yellow collie jumped through the open window of the Pontiac, into the back seat with the two girls. It appeared to be a happy meeting to both girls and dog.

I inquired of the garage owner as to where the dog belonged, and I was informed that it came from the white house across the street. Casually, and 100% kidding, I turned to the girls, and said, “Why don’t you ask the lady at the house if she would like to give you her dog.” I guess I was taken seriously, and the girls asked the lady if she would like to give them her dog, as their Grandpa lived on a farm and did not have one.

In a matter of minutes, one girl carrying a bag of Friskies and the other with a dog collar and leash returned with the dog to the car. The lady followed, and said, “Now I won’t have to worry about her getting run over. Her name is Nikki. She loves to ride; she jumped in my husband’s car three months ago, and he being unable to locate the owners, brought her home.”

The girls were excited to bring Nikki back to the farm. “Look Grandma, see what we brought to you for your birthday!” As Mildred had said, it must be a collie, female, and spayed, and so she was. Treasure mapping worked. We treasure her greatly.

We had to build a garage to house the Oldsmobile. The garage included a kitchen with sink, stove, and freezer to handle milk, since we had purchased a guernsey cow at an auction sale. We named the cow Betsy, and I fixed a place for her in the barn. I made space for a second cow the next year. Her name was Tricia. She was given to us because we saved her life!

It so happened that I was asked to care for some 2-year-old heifers that were soon to have a calf, with the owner taking the heifers home before they gave birth. One morning when I was about to feed the heifers, I found a nice Holstein heifer that had been in labor for a number of hours. The owner had no phone number, so Mildred and I did the next best thing, pull the calf, which we did. The calf was not normally developed, and the heifer with very little milk—she was well spent—got on her feet, and went into the box stall, a small room in the barn about 10 feet square, to lay down, and could not get back up.

I had to feed and water the laying down heifer, and gather the four stretched legs to turn her over to get her out of the manure. Five weeks later, on Easter morning, I found the heifer standing under the chute where hay is passed to the basement of the barn.

The owner gave the heifer to us, as we saved her life. We called her Tricia, after our President’s wife Patricia (Patricia Nixon). In the meantime, the calf had died. We now had two cows, but there was room for two, and with an old freezer for ground grain, a medicine cabinet attached to the corner, and a stool, we were in business with two cats that showed up at evening and morning.

Making maple syrup was really our first activity at the farm. The first day that we lived at the farm, Mildred and I drove north to Ogdensburg, New York, where they made sap evaporators, bought a 2 foot by 4-foot evaporator, and brought it home to the farm on a U-Haul trailer. Mildred and I had a great time doing what had to be done to prepare the sugar shanty, such as bricking in the evaporator using red brick from the house fireplace. When I mentioned to Rev. Bartlett about using the fireplace and chimney brick, his remark was, “I think you should use fire brick. It gets pretty hot.” So, I tore out all the red brick, and replaced it with yellow fire brick.

The maple syrup season starts about March 1st, depending on the weather required, most necessary of having a freeze at night followed by a raise in temperature to above freezing the next day. There are one to four spouts in a tree, depending on the diameter of the tree, and for each spout is hung a bucket to collect the dripping sap. The season of four to five weeks ends with signs of spring when the sap no longer drips.

It requires 45 to 50 gallons of sap boiled down to make one gallon of maple syrup. Maple syrup on pancakes is relished by everyone It is nature’s most delicious nectar. Its production is a happy season.

SPECIAL INTEREST AT SPRING VALLEY FARM

- Barn frame structure.

- Surrounded forested hills.

- 13 large maples.

- Eight 1,200’ oil wells—quit operating years ago.

- Gas engine at oil pump house.

- Wooden sucker rod—one whole one at barn.

- Cast iron ring for well drilling machine.

- End of scythe in maple tree at gate.

- Special hung gate—gate made in house.

- Beaver ponds—southwest end of farm.

- 3 bee hives—a swarm on house captured May 30th.

- Dead end road to south end of farm where I had 10 hives 18-20 years ago, where a bear tipped two hives four years ago.

- In house, fireplace replaced by bathroom.

- The tallest tree on horizon at left of barn, southwest corner of farm.

- Pictures of Mildred hung in kitchen.

- Picture map made by Mildred, Farm purchased in 1963 for $10,000.

- Hand railing at rear porch made of sucker rod ends—male and female.